ّIt’s just after noon on an unbearably hot July day in Manhattan and the Four Seasons restaurant is bustling. The establishment’s iconic Pool Room — not a metaphor the room is defined by the bubbling marble pool in its centre — is filled with famous (or at least New York-famous) regulars: Paul Walter, the collector; Thom Browne, the fashion designer; Lee F. Mindel, the architect; Martha Stewart, the Martha Stewart. On the edges of the room, a legion of young, well-dressed, interchangeably good-looking workers attends to customers at a furious but discreet pace.

Downstairs, meanwhile, in the restaurant’s “travertine marble entrance lobby,” a young woman is warned as she approaches the 52nd Street door that the venue is at capacity and she may not be admitted back inside should she leave. “But I’ll be right back,” the woman protests. “I really just need to go and grab something to eat.”

Two weeks earlier, this — leaving the scene of one of New York’s all-time great dining experiences to (presumably) choke down some sad street-cart falafel on a nearby bench — would only have made sense as an act of contrarian performance art. (Which has happened before at the Four Seasons; ask Anna Wintour or the anti-fur activist who once stormed her table with a dead raccoon in tow.) But on this day, it was just necessity. With its lease expiring in August, the restaurant had closed for business earlier that month. The luminaries upstairs weren’t gathered for a meal; they were bidding, lot by lot, on the restaurant’s furniture, tableware, and other objects — pieces of New York history. After 57 storied years, the Four Seasons was being auctioned off.

Mourning the demise of the Four Seasons is, technically, premature; the restaurant’s long-time co-owners, Julian Niccolini and Alex von Bidder, plan to reopen in 2017 in a new space just a few blocks up Park Avenue from its current location.

But that new space, which will be designed by Brazilian architect Isay Weinfeld, is for now an unknown. Meanwhile, the Four Seasons’ original home wasn’t just known, it was revered. Even the most acid-tongued corners of the New York media world — many of which spent the weeks leading up to the restaurant’s close charting its decline with a kind of gleeful schadenfreude — had nothing but praise for its interior. Certain blasphemies won’t be tolerated in this city, even from the Post. Speaking ill of the Four Seasons’ design is one of them.

That’s because the restaurant is — or was — beautiful. Not “beautiful” in the vague, encouraging way you praise a three-year-old’s fingerpainting or a Tinder date’s smile. Beautiful in a purely descriptive sense: a full moon rising over the ocean is beautiful; sunshine streaming through autumn tree leaves is beautiful; the Four Seasons is beautiful.

More concretely, the Four Seasons is a gleaming example of the International Style, a genre of modern architecture that revolutionized 20th century design beginning in the 1930s. After decades of architecture characterized by distinct but inevitably ornate decoration, the International Style marked a dramatic shift toward simplicity, geometry, sleekness. The Seagram Building — the stark, glossy tower that housed the Four Seasons for almost six decades — is today right at home in the metal-and-glass Stonehenge of Midtown Manhattan, but at the time of its construction in the 1950s, it was a radical act. If imitation is flattery, the Seagram Building is arguably the most thoroughly complimented American building of the past century.

When design began on the Four Seasons in 1956, while the Seagram Building was still under construction, the stakes were similarly high. The building’s architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and designer, Philip Johnson, boldly spent the restaurant’s then-record $4.5-million budget not on piecemeal, pricey embellishments, as was the norm, but on carefully considered, holistic minimalism. There were hiccups along the way; the artist Mark Rothko, for example, was commissioned to paint murals for one of the restaurant’s dining rooms but famously backed out because he grew uncomfortable with his paintings being exhibited for a restaurant’s chewing, distracted audience (you can now view them at the Tate Modern in London). Diners had to make do with a last-minute replacement — Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles — instead.

All this was in service of an artistic mission, notes the architectural critic Paul Goldberger in an essay commissioned for the Four Seasons’ auction catalogue: “to prove that modernism was capable of producing a room that would be the equal in grandeur of such great New York establishments as, say, Henry Hardenbergh’s Oak Room at the Plaza Hotel and Charles McKim’s main dining room at the University Club: places in which there was not only uplifting space but a sense that everything, from the architecture to the furniture to the tableware, came together to create a unified and beautiful whole.”

And now, 57 years after van der Rohe and Johnson’s gambit succeeded wildly, the beautiful whole was being dismantled. Yet the Four Seasons auction — conducted by the Chicago-based auction house Wright on July 26 and streamed live around the world out of the restaurant’s Pool Room — felt more like a memorial than a pillaging.

That was the result of careful planning, explains Richard Wright, the auction house’s founder and president (and namesake) — not to mention the lead auctioneer, who would preside over much of the event’s 14-plus hours. Because the Four Seasons is one of just four restaurants in New York to have been designated an interior landmark, every lot was reviewed and approved for sale by the New York City Landmark Preservation Commission, and certain pieces were acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other museums prior to public bidding. The goal, Wright says, was to enlist restaurant patrons and other design aficionados as de facto archivists: “This is one form of preservation. Not, maybe, the ideal form, but we are working to find good homes for these pieces.”

It’s hard to overstate how important many of those pieces are. Mies van der Rohe, Johnson, and their team of comparably perfectionist collaborators sought to create a gesamtkunstwerk — German for “total work of art” — or the type of interior whose greatness deepens and refracts as you move through it. The space and decor were intended as two equally important halves of the landmark’s whole. The Grill Room’s angular, sleekly modern bar stools, for example, subtly echo the Richard Lippold sculpture of gold-dipped brass rods suspended directly overhead — a kind of visual rhyme only furthered by the silver accents of the room’s tableware, designed by Garth and Ada Louise Huxtable. Here and elsewhere, the dynamic between the interior and its furnishings is a duet, not a conversation.

The day of the auction, sequestered in a press section near the front edge of the Pool Room’s pool (which, by the way, is louder than you’d expect, like a brook made of marble), I watch as many of those furnishings sell for big money very quickly. The impossibility of taking home what Paul Goldberger calls “the beautiful whole” seems no deterrent to the hundreds of bidders present, nor to the thousands who end up participating by phone or online. By the end of the day, Wright’s original high-end estimate for the sale — $1.33 million — has more than tripled, to $4.01 million across 650 lots.

Much, if not most, of that money comes through the phones lining the room’s north side. At his podium, Wright gestures like an air traffic controller, or Mr. Roboto, tracking the bidding as it ping pongs back and forth between bidders in attendance and phone surrogates. The very first lot — a bronze sign featuring the lightly modernist Four Seasons logo designed by Emil Antonucci — soars to a closing price of $120,000 from an estimate of just $5,000 to $7,000. Mies van der Rohe’s low-slung lobby Barcelona chairs go for $21,250 (estimate: $5,000 to $7,000). Banquette No. 32 from the Grill Room — where Philip Johnson sat nearly every day for years and which also hosted Princess Diana on her only visit — reaps $35,000 (estimate: $3,000 to $5,000).

In an auction world dominated by high-end, record-breaking fine art sales, those numbers almost seem modest. To put them in perspective, look at the results posted by Paris’s Michelin-starred La Tour d’Argent, which auctioned off 670 lots worth of tableware, furniture, and spirits in May and netted about $825,000. (Granted, La Tour d’Argent wasn’t closing, just renovating.)

Money aside, the scope of the auction on a purely logistical level was astonishing: 650 lots sold in an event that stretched from 10 a.m. until past midnight. “How the hell do you prepare for that kind of marathon?” I ask Brent Lewis, the director of Wright’s New York location (in more or less those exact words). He chuckles politely, and instead of directly answering the question raises the stakes even further. “Until last Saturday night, this was a working restaurant, incredibly busy — people morning, noon, and night,” Lewis said. “Usually when we do an auction, we work slowly to catalogue and count and photograph everything — here it was counting things on the way through the dishwashing machine.”

The process took about three months, but Lewis says working alongside the staff in the still-operational restaurant was an invaluable opportunity to deeply understand the history and narrative of the place — as well as to stumble across hundreds of brandy snifters in storage, long thought lost to time. (They sold in sets of 12; the two most successful lots — No. 155 and No. 156 — netted $4,063 each.)

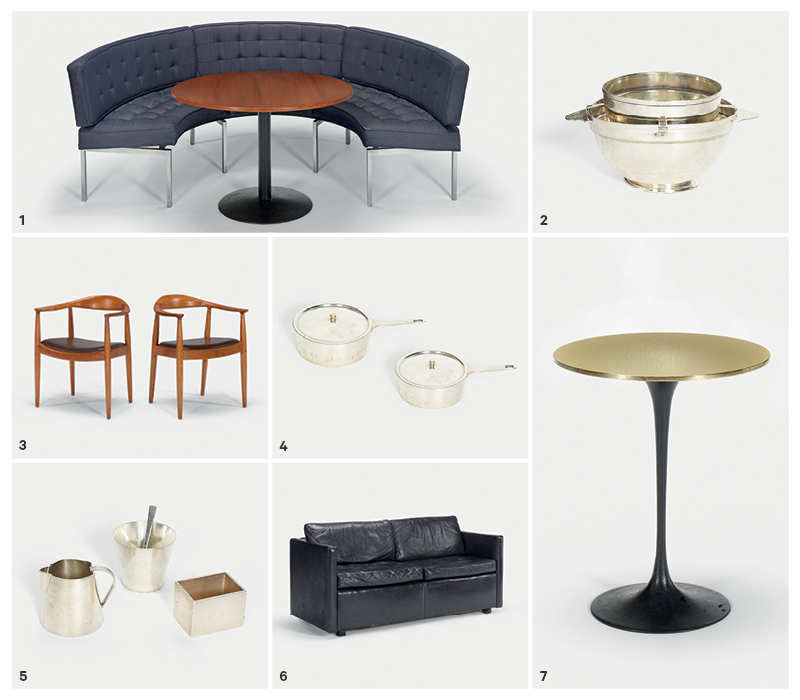

1. PHILIP JOHNSON GRILL ROOM BANQUETTE AND TABLE. SOLD FOR: $62,500. 2. HUXTABLE CAVIAR BOWL FROM THE FOUR SEASONS. SOLD FOR: $8,125. 3. HANS WEGNER CHAIRS FROM THE MEZZANINE OF THE GRILL ROOM, PAIR. SOLD FOR: $6,875. 4. HUXTABLE SAUCE POTS, SET OF TWO. SOLD FOR: $3,250. 5. HUXTABLE CREAM AND SUGAR SERVICE. SOLD FOR: $3,750. 6. PHILIP JOHNSON PERCHING SOFA. SOLD FOR: $10,000. 7. EERO SAARINEN CUS- TOM TULIP TABLE FROM THE BAR OF THE GRILL ROOM. SOLD FOR: $35,000.

“A lot of what we do is storytelling,” Lewis says. Spending so much time in the trenches, soaking up anecdotes about Jackie O and Bill Clinton, among literally hundreds of others, built up the Wright team’s understanding that “every object, every person” had a story. “It enabled us to understand in a much deeper way what the restaurant means, which allows us to do our job perhaps not more efficiently but certainly better.”

I hear this sentiment, in one form or another, from multiple people: that the meaning of the Four Seasons is in its stories, and the stories create its meaning. What seems at first like circular logic gains a certain resonance as it becomes clear how deep the well of Four Seasons stories runs — and for how many people.

Alex von Bidder, the co-owner, tells me that well is to some extent untapped. Media coverage of the Four Seasons tends to hinge on anecdotes about glamour, money, power, he says, and that’s understandable. They’re good stories, and his customers are important people. But “a more dynamic and a more true story,” he says, has to incorporate, for example, his 140 staff members who, are “as interesting or possibly more interesting than the headline names.” “It’s not about Julian [Niccolini] and me,” he says. “It’s about everyone else.”

This isn’t lip service. As if to prove his point, von Bidder immediately introduces me to Trideep Bose, who’s worked for the restaurant since 1987 and has served as a manager since 1997. Over the next 15 or so minutes, Bose’s tone grows from politely deferential to palpably enthusiastic, buoyed especially by a series of questions about his rise through the ranks to become a beloved figure among guests.

8. HUXTABLE CUSTOM FLATWARE, SINGLE SERVICE. SOLD FOR: $1,750. 9. SHALLOW SKILLET, PAIR. SOLD FOR: $2,000. 10. LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE BRNO CHAIRS, PAIR. SOLD FOR: $6,875. 11. COFFEE SERVICE. SOLD FOR: $1,536. 12. BREADBASKETS, SET OF TWO. SOLD FOR: $6,250. 13. FOUR SEASONS ASH- TRAYS, SET OF FOUR. SOLD FOR: $12,500. 14. PHILIP JOHNSON BANQUETTE 2 FROM THE GRILL ROOM. SOLD FOR: $16,250.

“I come from a very small town in India. In my wildest dreams, I did not think I would meet any of these people,” Bose says and, softening on his earlier reluctance to speak about celebrity clients, name-dropped Ian Schrager, “just for an example.” “He used to own Studio 54, and you know Indians are big into clubs and all that. And I know Ian Schrager personally. When my friends back in India found out, they almost fainted.”

And like that, Bose is off and running, relating a more detailed version of the Anna Wintour/dead raccoon story than seems to exist on the Internet (The raccoon was frozen and, when it hit the table, “made a nice thump!”) and speaking reverently about the time he met Bill Clinton (“He repeated my name flawlessly”).

No circular logic here: the Four Seasons does matter because its stories matter. Bose’s stories, von Bidder and Niccolini’s stories, Wright and Lewis’s stories, Anna Wintour’s stories, even that poor young woman just trying to escape the auction to grab one lousy sandwich — her stories, too. Taken together, they form a deeply convincing argument for the importance of mythic spaces like The Four Seasons, a heightened forum for the rich and powerful that nonetheless gifted memories indiscriminately to all who came.

It’s appropriate, then, that the Four Seasons — this incarnation, at least — went out with an auction, distributing pieces of itself far and wide around the city and the world. It had already been doing that for half a century, symbolically. Great stories are meant to scatter; maybe great restaurants are, too.