He’s been inside too long, confined to the underground tunnels connecting hotel and convention centre, breathing canned air, shaking hands and talking shop with strangers. He’s trying to make as quick and seamless a getaway as possible, dragging his luggage — he has a flight to catch later today — through the unrelenting throngs of the Toronto International Auto Show, which this year coincides claustrophobically with the NBA All-Star Game. The epicentre of both seem to be this very hotel lobby, the entrance of which is lined with metal detectors and patrolled by security guards who are far too good at their jobs. The idea is to keep the riffraff away from the celebrities stowed safely within — the basketball players, that is, not the premium car designers. If only the guards knew who they were dealing with.

We shake hands across a velvet rope and hurry outside to our waiting car — a 2016 Jaguar XJL — and pause in the chill of a late winter cold snap. I see him revel in the frigid air, swallowing its freshness. I worry about the plan. We’re on our way to the Art Gallery of Ontario, to show Callum, a proud Scot, a bit of Canadian culture — and to get his take on the city’s best architecture (our precious, very own Frank Gehry) and visual art. As lead designer at Jaguar, Callum does more than just draw cars for a living. He’s an artist, an attender to details, a craftsman. He’s a man who imbues motion into solid steel. He’s the Steph Curry of automotive design. But maybe Ian Callum doesn’t want to go to the art gallery. Maybe he wants to go ice-skating or shoe shopping or something — anything — that doesn’t involve getting into yet another car and then another big indoor space.

•••

We get in the car. I should have known that Callum would relax in the back seat. After all, he designed it — the whole car, actually, from the distinctive taillights (“We got a lot of hate mail for those,” he says, “because they wrap up and over the trunk instead of around the side. But I don’t care. I like them”) to the dashboard temperature controls, to the heated back seat we’re in right now. He saw it through every sketch and rendering and clay model until it became Jaguar’s latest luxury sedan. So he knows what this car is meant for, which is exactly this: going from one place to another in almost unconscionable comfort.

As we drive, I get the full tour of the Jaguar from the man who made it. It’s a little like getting a tour of Falling Water from Frank Lloyd Wright or watching Jaws with Steven Spielberg. He talks about the boomerang-like line that wraps around the car at shoulder height, almost single-handedly propelling the car forward; he talks about the navigation system, the only part of the car (physical, mechanical, digital) that Jaguar didn’t design in-house, the choppy visuals of which still drive him mad; he talks about the vaguely Star Wars–-like round air vents, which light up in soft blue LED at night, because why not?

The further away we get from the convention centre, from the unruly sameness of downtown skyscrapers, and the closer we get to buildings — actual, discernible buildings — the more relaxed Callum seems to get.

•••

Inside the AGO, somewhere in the endless rooms of early Canadian art, Callum spots a painting with the letters RCA on its gilded frame. “What do those letters stand for, do you think? I wonder if it’s the Royal College of Art. That’s where I went.”

Callum’s road to the RCA, and then on to Jaguar, was fairly direct, if unconventional. He grew up in the small village of Dumfries, Scotland, hardly a design or automotive centre. He didn’t spend much time going to art galleries or drawing class. But he fell in love with the cars he saw on the street. “It’s always been Jaguars,” he says. “We didn’t get to see many really fancy cars where I grew up. But Jaguars were always around. My dad never had one, but somehow lots of his friends managed to. I thought they were the most incredible things.”

Naturally, he started drawing them — every model, including ones that didn’t exist. He sent his drawings to the technical director of Jaguar at the time, W.M. Heynes, who replied with a polite — and apparently encouraging — rejection: “Your general conception and ideas are good…and you should endeavour to take this up at school at the earliest possible moment….”

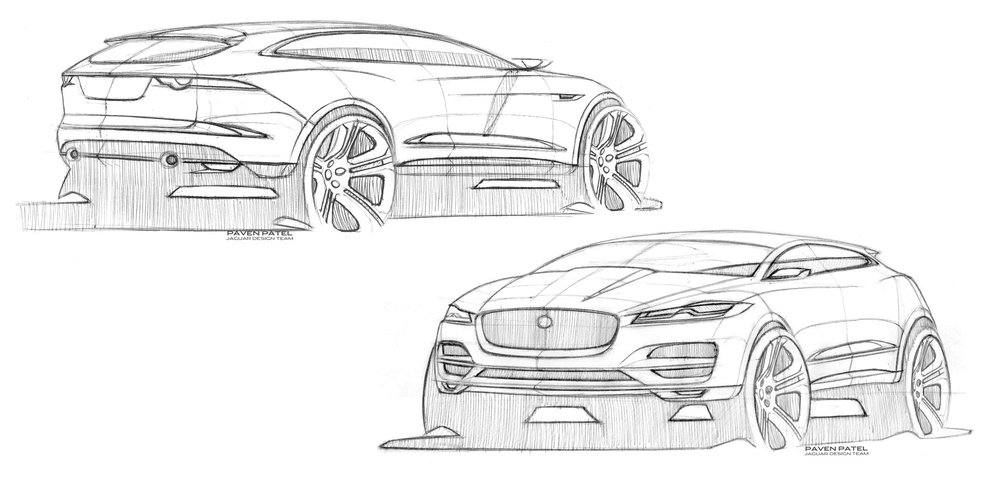

Callum took the advice to heart and studied vehicle design throughout his graduate and post-graduate years. Eventually he landed at Ford, where he tinkered with Transit vans and Fiestas — hardly glamorous stuff, but it got his designs from paper and pen to sheet metal and glass. And it was enough to get his name out there. After 11 years, he took a massive leap: he and a couple of design pals banded together and started their own firm, turning out the Aston Martin DB7 and Vanquish — a couple of Brosnan-era Bond cars that stand, to this day, as Callum’s calling cards. You can see elements of them even in his latest work — everything from the XJL we were cruising around in to Jaguar’s newest toy, the F-Pace sport utility vehicle. Much like you can instantly recognize a Monet or a Picasso or a Basquiat, Callum has, over his 30 years in the industry, developed a clearly defined aesthetic. You see it in the swooping lines of his fenders, the gently curving silhouettes that run from nose to tail, the attention to detail, and even surprise, like bursts of unexpected colour in gloveboxes or cup holders. Call them motifs — the man is an artist, after all.

•••

“I love John Turner,” he says. “His paintings are so full of light — and the light has this way of moving.”

We’ve missed the Turner exhibit by two days, so Ian Callum won’t see his favourite painter’s work today. He’ll settle instead for something a little more New World, trading in the English country landscape for the rugged Canadian one. We’re standing on the second-floor gallery at the AGO, looming over Lawren Harris’s daunting Lake and Mountains, and I’m doing my best to summarize a century of Canadian art, which somehow boils down to an unsatisfying misunderstanding of statistical mathematics: give seven men seven easels and seven years alone in the wilderness and one of them will almost surely draw a masterpiece.

Callum is puzzled by the piece, trying to see it in its context. He looks at it with practiced eyes, studying the brush marks, the way the light hits the bright white snowcaps on the mountains and skirts across the blue of the lake. “I think I get it now,” he says. “And you know what else? It’s been so long since I’ve been to a gallery, really looked at paintings. I’ve been inspired. I think I’m going to take up painting again when I get home.”

That’s the kind of thing lots of people say in the presence of greatness, the kind of remark you’d never think to follow up on if it came from almost anyone else. But you can tell that Ian Callum means it. The man is clearly looking for an outlet. A few more steps, another Harris painting, an A.Y. Jackson, and suddenly we’re getting somewhere.

“The truth is, I really want to design other things,” he says, his face lighting up in a way it hasn’t quite all day. “I mean, don’t get me wrong: I love designing motorcars. But I’m up for a challenge. I want to design a pen. Maybe a camera. My big, secret dream would be to design a scooter. But I’m not sure I could get Jaguar to let me do that.”

•••

Looking out the big glass windows onto Dundas Street, watching Ian Callum watch the streetcars shuffle past in the cold, it’s clear that he is, in fact, truly restless. It’s a restlessness that comes with great talent: to do more, to build more, to get to the next unforeseen place.

Callum’s phone vibrates in his pocket. He takes it out and shuts it off without looking at the number. As he puts it on the table beside his rapidly cooling green tea, he pauses, locked in contemplation on that little silver brick.

“What do you think they’re going to do?”

“Apple?”

“Seems they’ve lost their way, haven’t they?”

He would know. In his long career in the design world, he’s made some high-powered friends — including, Jony Ive, Apple’s chief design officer.

“It looks like their next step is cars — but I don’t think they know just what goes into building a car. They’re brilliant at computers, but cars are other beasts altogether.”

Another pause.

“I think Jony’s a bit restless, too.”

•••

Outside, Callum graciously poses for a couple of pictures with the car. Clearly, he’s done this before. He stands at the exact right angle, his leg falling seamlessly on the fender, a perfect car designer’s pose, one that says, humbly: this is one of mine. He hops in the driver’s seat for a few more snaps, and when we join him back in the car, The Eagles are blasting through the speakers. Really blasting.

This is a man, after all, whose personal fleet of cars back home in England includes three vintage Mini Coopers and a couple of greased-up American muscle cars. He might be refined in taste and in demeanour, but don’t forget that Ian Callum likes his cars fast and his music loud. He’s a huge music fan, he explains. Especially, and above all, David Bowie. “He was my greatest inspiration,” he says. “I grew up with Ziggy Stardust. And the music, the persona, it all just said ‘dream big; dream wild.’” And never, ever stop.