Karim Habib has just uprooted his entire family and moved to Tokyo. A bit of culture shock is to be expected, but the Canadian automotive designer hired to reshape Infiniti is boundlessly enthusiastic about his new home.

“Japanese residential architecture is unbelievable… I still don’t understand how it functions, how some businesses actually survive,” Habib says. He talks about walking the narrow streets, the amazing variety of great food, how you might catch a glimpse of a perfect Parisian bistro through some anonymous alleyway. The density is on a different scale. The layout, the hub-spoke structure of most cities, simply doesn’t apply to this sprawling metropolis with a higher GDP than all of Canada.

“Some houses have a metre between them. How do you make sure there’s daylight? How do you keep your privacy? It’s fantastic stuff.”

This past summer, he and his wife moved with their two young children (both now counting in Japanese, for the record) from Munich, where Habib had been BMW’s head of design since 2012. You know his work, even if you don’t know him. He’s responsible for the look of every BMW in showrooms today, and arguably defined the German company’s design direction with the 2007 CS Concept. You can see Habib’s influence in copycat designs from other brands. That Infiniti managed to lure such a high-profile designer away from a top job at BMW tells you the Japanese luxury brand has bigger ambitions.

“The sheet of paper is a lot emptier here, so that really allows us to be very creative,” he says during our meeting in Tokyo. “The idea that I can be one of the many factors in rebuilding that brand — I love that. That’s what drives me.”

With Habib at the helm, Infiniti is poised to compete directly against the established German luxury brands. “To be honest, I think it’s now or never,” he says. “I’m here to make that happen.”

Habib has before him a unique opportunity to reinvent a global brand and — if he can pull it off — to put his stamp on the history of automotive design. The timing couldn’t be better. The triple threat of electrification, mobility services, and self-driving technology has left the door wide open for a total remaking of the automobile. How should a car’s interior function when the driver doesn’t need to drive? Do cars still need windows? Steering wheels? Suddenly, it’s all up for debate. The revolution will take place over the coming decades. At Infiniti, Habib gets to start from a blank slate, working up answers to these big questions.

He is accustomed to reinvention. He grew up in Montreal, but was born in Lebanon just before the Civil War in 1975. His parents took the family to Iran, only to move again once the Revolution broke out. They lived in France for a year, and then Greece, before finally moving to Canada in 1981. There, Habib studied mechanical engineering at McGill; mechanical engineering at McGill; later, he pursued design at the prestigious Art Centre College of Design at its campuses in Switzerland and California. He was hired out of school by BMW, and moved to Munich shortly thereafter, rising quickly through its ranks.

“Japanese residential architecture stands out not for the sake of standing out, but because they try to solve a problem in the most sincere and honest way. That’s the way I would like to do it. That’s the way I would like people to think of Infiniti.”

He’s fluent in French, German, English, and Italian, and is working on Japanese. From a young age he learned to adapt to changing surroundings. “Still, for me, my hometown is Montreal,” he says. “I’ve lived now, actually, longer in Germany than I did in Canada, but you know, it’s those formative years.” Whenever he’s back in Montreal, he returns for a burger and shake at his favourite diner, B&M, in the city’s Mile End neighbourhood.

“[Canada] opened the world to me. It gave me an education. It gave me an openness to the world, and a tolerance and understanding of so many different cultures. There’s a strong artistic sense, and a really interesting, creative, hands-on way of doing your own thing in Canada that’s great.”

In Tokyo, he’s discovering yet another new artistic sense. He’s drawing fresh inspiration from the work of Naoto Fukasawa, a famous industrial designer best known for the candy-like “Infobar” cellphone. “He did some very minimalistic, very pure stuff,” says Habib. He also likes the work of Tokujin Yoshioka, who plays with different manufacturing techniques, notably a glass material that makes furniture seem to disappear into its surroundings. And Jo Nagasaka, of the architecture firm Schemata, whose houses look unfinished at first glance, with raw plywood surfaces. “It’s really interesting,” he says, “working with inexpensive materials and still managing to do really beautiful stuff.”

It all seems to feed into the humble, handcrafted type of luxury you find throughout the country. “This Japanese aesthetic that is about reducing — not removing, but reducing to the essence,” he says. “It’s omotenashi, a very classic understanding of Japanese hospitality… There’s this human craftsmanship aspect, where you appreciate that there’s somebody behind the minimalism.”

That certainly points to a different approach than we’ve seen thus far from any of the German luxury automakers, whose vehicles all have a kind of machined perfection, a detached coolness. “We’re a new brand,” Habib says of Infiniti. “People are going to come to Infiniti because of something we can offer that makes life a little better. This aspect of generosity, of service… I think there are a lot of things we can do.”

How exactly this will translate into a new design direction for Infiniti is too early to say. The Q Inspiration concept, unveiled at the Detroit Auto Show early this year, provided some clues, but it will be a few years yet before the first Habib-styled Infiniti hits showrooms. He’s clearly onto something — he just hasn’t quite pinned it down yet.

“I don’t know if it’s going to shock, but it needs to stand out.”

And that’s another thing Habib’s new surroundings have taught him. “Japanese residential architecture,” he says, “stands out not for the sake of standing out, but because they try to solve a problem in the most sincere and honest way. That’s the way I would like to do it. That’s the way I would like people to think of Infiniti.”

For Habib, this approach extends beyond the look of the cars. It will inform how Infiniti tackles the big questions about the future of the automobile: about self-driving vehicles and cars-as-service. When it comes to electric vehicles, Infiniti has one big advantage. As a sub-brand of Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, Infiniti can draw from the group’s expertise as the world’s largest manufacturer of electric vehicles. They’ve done the R&D — it’s a question of when the market is ready for Infiniti to put it to use.

“The opportunity is great. We have to grab it. More than grab it — it has to bring a new experience, or offer to make your life better in a different way.”

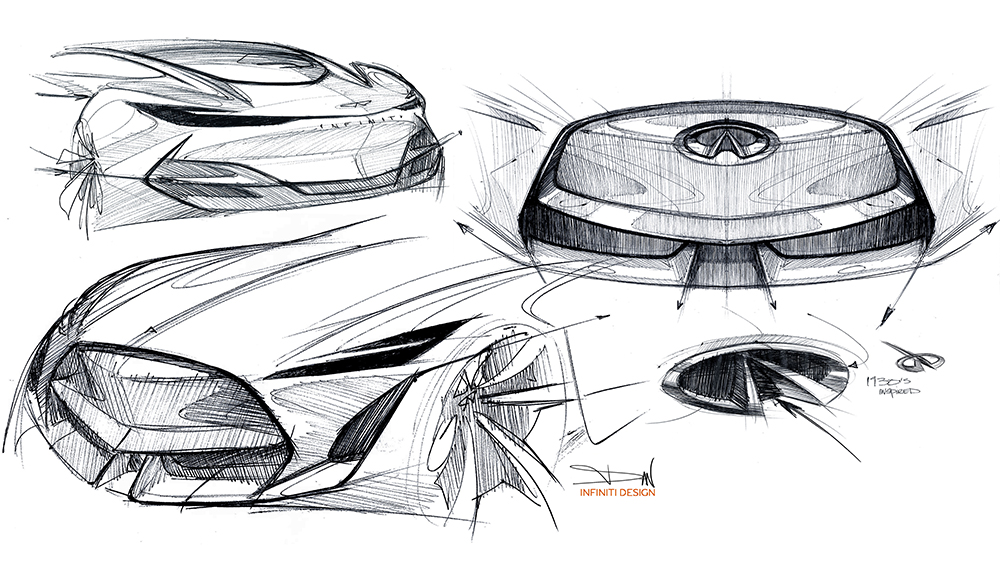

In the studio in Yokohama, he and his team are busy sketching, exploring new forms and shapes. He’s more hands-on than he was at BMW. “Just this week, we milled something — a new model. I just saw the first impression and I was like, Yes. It’s got something. There’s a unique spirit to this.”

As Habib begins life in yet another city, he’s learning a new visual language, and adding to an expertise learned in Canada, as well as the Middle East, Munich, and California. This is inspiration in the raw: a brain trying to understand new stimuli. “I like that feeling of newness,” he says, “a new vocabulary, a new way of solving problems.”

We’re curious to see the results. “Me too,” he says.