In the last half century a great number of small companies sprung up all over the world which planned to produce supercars good enough to rival the best of what Ferrari or Lamborghini could offer. Some of the designs remained for ever at the rough sketch stage, others culminated in some sort of small-scale production. Most of those companies have ceased to exist and their products are impossible to see in the wild. The Ascari brand, however, is a bit different.

Everything begins with Mr. Klaas Zwart, the Dutch entrepreneur born in 1951, who made some money in the oil business. He did not have his own oil fields, but he designed and built equipment needed for drilling, and holds at least four international patents in that area. Instead of spending his millions on something silly, he started to race cars and became a competent racer very rapidly, even taking part in the 24 hours of Le Mans several times. After some time he purchased several Formula 1 cars from the early 1990s (among them a Benetton and a Jaguar) and drove them with skill and gusto.

Moving his cars and mechanics between various racing circuits in Europe just to practise probably got on his nerves, so he decided to build his own race track. This is how the Ascari circuit in Andalucia came to be in the year 2000: it is a compilation of the best corners from various tracks, including the awesome Paddock Hill Bend from Brands Hatch and the scary Karrussell from the Nürburgring. At first Zwart kept the track for himself and rejected all offers from manufacturers who wanted to organize press launches there; finally his resistance to such advances waned and the first events were laid on by Maybach and Bentley, followed by numerous other car companies. Today, the track is a kind of club where members can train using rented cars, or, alternatively, they can bring their own supercars in order to enjoy them in safe, controlled circumstances.

The Dutch businessman also bought a company which he named Ascari Cars and invested heavily in the creation of a new supercar, engineered according to his own dreams and demands. He financed a special production facility in the UK, in Banbury (that is very close to the legendary location of Prodrive), where 30 specialists were to build the Ascari KZ1 (KZ standing for Klaas Zwart, of course) in series, with over 1000 man-hours going into the construction of each car. As we know, lots of people who never buy supercars love to criticize them on the internet, most often for the use of off-the-shelf interior components from ordinary vehicles. Therefore the Ascari team decided to machine the air vents and all kinds of rotary switches out of billet aluminum. Cheap that was not. The chassis was designed by Lotus Engineering, the engine came from the E39 BMW M5 (but with bespoke software which liberated an extra 100 horses, making 500 hp the power output of this extraordinary engine). Perfecting the car took a very long 5 years.

Making plans is much easier than making cars, but various internet sources still insist that Ascari manufactured 50 of those cars. Unfortunately nothing is further from the truth. Recently one of the cars appeared at an auction and the buyer was due to receive a letter with the car, a letter signed personally by Klaas Zwart, certifying that the purchased vehicle is one of FIVE ever made. Five! Why did the production stop and why was the company liquidated (the Haas F1 team now occupies its facility)? Well, each KZ1 cost approximately £400,000 to build, and the retail price was set at £235,000... Economics always win against optimism. What is worse, the car offered at the auction was valued at between 200k-300k pounds, so obviously there is no value growth with time. And that is sad indeed.

I am very luck to be friends with a gentleman who owns one of those five Ascari KZ1 cars and he let me drive one very hard at the Guadix racing circuit in Spain. It was a sunny day, and the blue sky in the background was bisected by the jagged teeth of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Ideal conditions. The blue Banbury car looked great. The billet aluminum switches really seemed beautifully finished, but they were definitely a symptom of overkill: I never cared if a Ferrari I drove had Fiat switches, as long as they worked, and the steampunk tendencies of the last real TVR cars were simply laughable. But... the bodywork is beautifully finished, similarly the interior, zero sloppiness and lots of precision. It just does not have that "car-built-in-a-shed" look. So far, so good. I quickly recheck the paper stats: 0-100 km/h in less than 4 seconds, 0-160 km/h in 8 seconds, top speed over 320 km/h, 500 horsepower, 500 Nm, 1300 kg, huge AP Racing brakes. Promising.

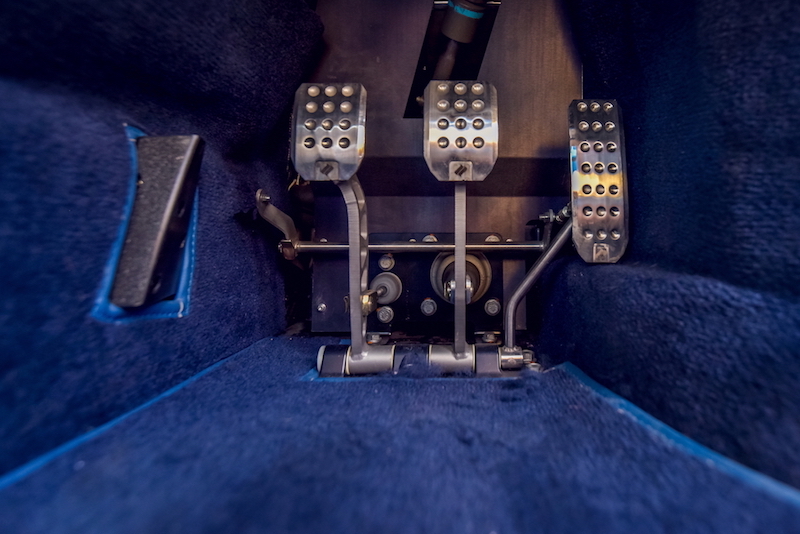

I slither behind the wheel and am immediately aware that something is wrong. While the seat can be adjusted ot fit me, my feet reach a narrow opening in the footwell, between the wheelarch and the pedals. This is definitely a packaging issue as in many supercars built by the small companies the same problem occurs; it is also present in earlier Lamborghinis. The driver's feet and the necessity to operate pedals are afterthoughts with the engineers scratching their heads while trying to create enough space for a front wheel to move up and down together with the suspension and also to turn left and right. The less compromise available within the engineering framework, the more horrible the ergonomics become.

Today many companies "solve" the wheel packaging issue by deliberately limiting wheel travel so that the wheels would fit the vehicle. Anyway, the packaging on the Ascari seems to be a major omission if the car was "perfected" for five years. Perhaps the engineers were constrained by the chassis, I don't know. What I do know is that it is impossible to properly heel and toe in this car, and I obviously lack an extra joint in my right leg right above the ankle. In a two-pedal car that would not be an issue, but in this one it is. It takes away a lot of the pleasure of driving it. It is like being served a splendiferous dessert in a good restaurant, but handed a massive ladle to eat it with.

And that is a great pity, because the rest of the KZ1 is great. The body has lots of torsional stiffness which made it possible to tune the suspension really well. The slight understeer give way in a corner to a totally neutral attitude, and the steering tells me exactly what the front tires are doing: essential in a car with no electronic driver aids. The engine is a marvel too, not just because I love naturally-aspirated engines, but because it fits the capable chassis, being able to instantaneously deliver as much torque as the driver needs at any time. The gear lever is unnaturally tall, but the ratio changes are all instinctive and precise.

I try to probe the chassis a bit more, attacking the racing kerbs more aggressively, but the beautifully damped suspension soaks everything up and helps keep the car stable in violent transitions. This is one very capable chassis, with immense poise and fluidity of reactions. Pity that only five were made and that the chassis was not developed further, and the packaging improved. The impossibility of performing heel and toe detracts from all the advantages of this otherwise harmonious car. It is puzzling why this area of development was overlooked or ignored. A really good car with one major drawback. I am glad that Mr. Zwart spent his money on this rather than some banal luxury yacht, and I am very glad I have been able to drive it. Remember, only five were made...

Words: Piotr R. Frankowski

Images: Juan Gabriel Rueda