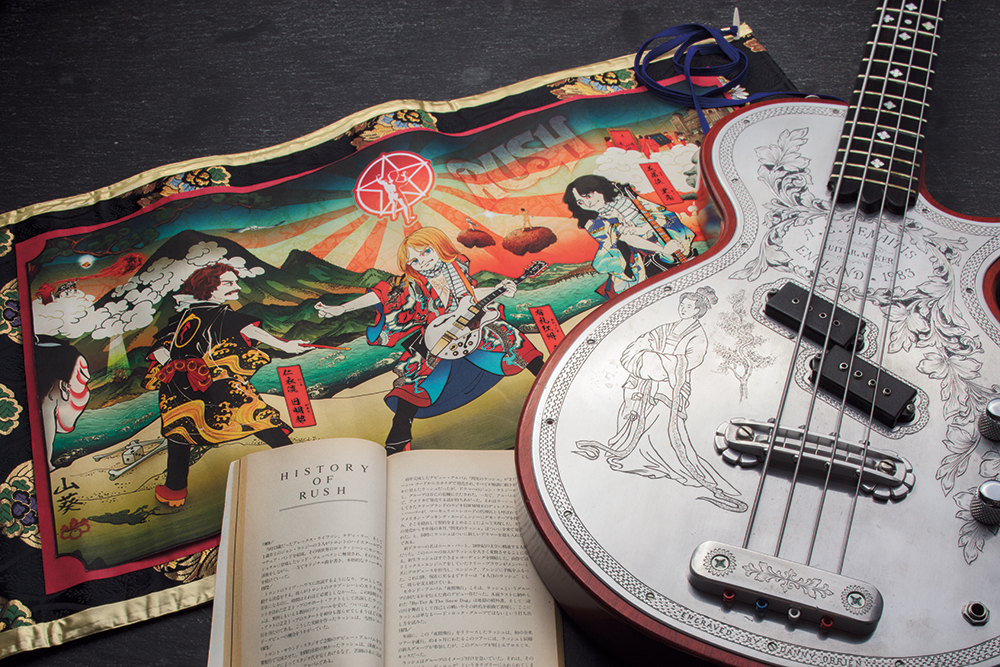

After 40-plus years of slappin’ da bass with Rush, Geddy Lee thinks it’s about time his instrument of choice gets its moment in the limelight. His weighty new tome, Geddy Lee’s Big Beautiful Book of Bass, showcases 250 vintage bass guitars from his personal collection, photographed by celeb photographer Richard Sibbald. Featuring musings by the Rush frontman and tête-à-têtes with his contemporaries (Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones and the Stones’ Bill Wyman), it’s the definitive take on the four strings — and an excuse for the Gedster to flex his almighty nerdiness. “There are so many things we discovered about these instruments that other guitar geeks may not realize, because it’s very rare that anyone has so many of them in their hands the same time to compare,” he says. “I tried to make the book interesting for the geek like me but not overwhelming for the casual person.”

Pfft, as if there are casual Rush fans. Rest easy, analog kids, Lee’s book is rife with all the obsessive, excessive attention to detail you’ve come to expect from Canada’s prog overlords. Over nearly three years, Lee and co-writer Daniel Richler went to manic lengths — from consulting a roundtable of bass experts for historical accuracy to spending countless hours revising countless drafts (“My editor said the initial manuscript was the longest she’d ever received”) — to craft 408 pages of intricate, glorious bass-dork porn. Give Lee free will, and he will choose to go waaay down the rabbit hole.

We caught up with Geddy to chat about his vast bass collection, his obsessive personality, his dogs, marijuana legalization, the future of rock, and what everyone really wants to know: will the members of Rush ever play together again?

Hey Geddy! How’s your day been going?

Oh, my day’s been fucking crazy. I have two terriers that both injured themselves at the same time and had to have surgery on Friday. They just came home from the hospital and are limited in their movement. It’s the craziest thing I’ve ever heard of. Both of them were chasing a squirrel and they both tore their cruciate ligament, in their hind leg, at the exact same moment. Can you believe that? It’s just a fucking nutty story.

How is that possible?!

I don’t know! But there they are. They both had surgery at the same time and they’re both laying in my house. You can’t let them roam anywhere and they won’t leave my side. They’re both at my feet staring at me right now. [Laughs.]

What are their names?

Stanley and Lucy Wasserman. I didn’t think it was fair to not give them full names.

Why Wasserman?

Why not? [Laughs.] They act like an old Jewish couple, so I gave them the names of an old Jewish couple. Lucy bitches at Stanley all the time and it’s pretty funny.

He’s always in the doghouse!

Yup.

So, I caught you on your last tour with Rush back in 2015. What have you been up to these past few years?

Well, I’ve been obsessed with this book, really. It’s kept me much busier than I ever would have guessed or desired, but it turned into an obsession. I mean, obsession is sort of who I am. I’m an obsessive guy. Being the detail-oriented person I am and have always been in Rush, it naturally bleeds over into any project I do outside of Rush.

I found the process really interesting. I took it to what I believed was its necessary conclusion, and that was fanatical attention to photographing the instruments so that they stand as pieces of art, as well as useful tools for making music. That was the challenge and Richard Sibbald, the photographer I used on the project, really rose to the occasion and blew us away with his photography. Then the other challenge was, “I guess I have to put some words in this book.” I had to find a way to inform without being pedantic or didactic. It wanted to make it fun and conversational.

How many basses in total are in your collection?

Ah, I don’t know! There’s 250 in the book and that’s not the entire collection — that also doesn’t include my guitar collection. I actually also collect six-string guitars, and I snuck some of those in the book as cameo appearances for historical context. But there’s over 80 of those stashed away somewhere, so, you know, my sickness is deep. I have a lot of instruments.

So when did this obsession begin?

I think it began around 2012, really. For most of my career, I wasn’t that guy — I wasn’t that guitar geek. I used the instruments as tools. I picked the ones I felt could get me the tone I needed, and I shut myself off from anything that distracted from the sound I had in my head. But one day I was in rehearsals in L.A. and a music store wanted one of my instruments. They offered me a vintage instrument in exchange. And, of course, I didn’t want to part with one of my instruments. Why would I do that? But we ended up coming to a deal for one of my backup instruments and I thought it would be a cool idea to have a Fender bass from 1953, the year of my birth. So when I got that in my hands, I thought, “Wow this is really cool!” I started getting that feeling I get when I find an old baseball from the 1920s or a great vintage of wine: you want to know as much about it as you can.It’s part of what makes a collector so obsessive; you don’t want to have a thing unless you fully understand what the thing is.

So I started doing research and in that same deal I also got the 1968 Fender Telecaster Paisley bass, which was a cool, funky, retro, psychedelic-era bass. Those two things stared back at me and sent me into a mode of investigation. I went down the rabbit hole and seven years and over 300 instruments later, here I am.

“I’m a bit of a hedonist, so I want what I want and then when I have it, I want to be able to justify to myself why I wanted this thing. So then I become obsessed with learning everything about it. “

Let’s unpack your chronic obsessiveness. As you mentioned, you love collecting baseball artifacts and wines, too. Even in your music, you don’t take half measures — you explore things to their fullest extent. Where does that tendency come from?

I really don’t know! It’s a good question. I can explain the obsession, but I can’t explain the reason for it. Part of it is justification. I’m a bit of a hedonist, so I want what I want and then when I have it, I want to be able to justify to myself why I wanted this thing. So then I become obsessed with learning everything about it. To me, they’re windows into history and in a way, windows into culture. When I started collecting baseballs, I felt it was bringing me closer to the game. I wanted to really understand the history of the pastime. And so my baseball collection was a window to American history for the last 200 years, and it’s very connected to what goes on in that country and that culture. That was beautiful; it was like reading the ultimate historical biography of the game.

And the same thing with wine! I mean, wine has the added benefit of giving you a hedonistic and visceral pleasure. They taste good and they get you high, so that’s an added bonus. But there are so many wine regions of the world. It’s really important, if you’re going to collect something, to be specific about what you’re collecting. Otherwise, you’re a hoarder. There’s a fine line between a collector and a hoarder. The difference is having a specific goal in mind and building a collection that has some sort of meaning. So with wine, it took me years to refine the things I really love the most. I eventually ended up being a consummate Burgundy nut. But the pursuit of knowledge and understanding winemaking and wine regions has been a great bonus to my life, because it drove me to go to these places where wines are made — to go to these vineyards, take my family, take my dogs, and go hang out in a different part of France any time I could get a summer break long enough. The one obsession that my wife and I both share is we’re travellers. We have the travel bug; we can’t sit still for too long. So the more things you can find to do along the way, the better.

Makes sense!

I’m also a nerdy birdwatcher and that’s another reason to travel. It’s sort of led me to become an amateur bird photographer, which I do in my spare time. You know, the world is full of little things that reveal a lot about the places you are, but also reveal things about yourself and about your nature.

Which bass in your collection has the most interesting story?

My favourite basses are the ones that come with some sort of tale about who played them. Of course, I would think every guitar collector loves what they call single-owner guitars. You want to find an instrument that one guy owned his whole life. And a lot of collectors are after mint instruments that one guy owned and barely played. I like those because they’re more valuable and pristine, but I love instruments that have lived a life. I’ll give you an example. I found these two 1964 Fender Jazz basses in Dakota red, which is not an easy colour to find from that era. They were both identical with one profound exception: one was absolutely mint, meaning it had never been played. It had been under somebody’s bed, probably. Then, the other was owned by an Irish fellow who played one in a showband his whole life. This was his bass he played in all the clubs and all the bars. Literally, when I opened the case after purchasing it, you could smell the beer and cigarettes. In the case was a photo of him and his band when he was younger and had just bought the bass, so you can see the bass as it was and as it is now, sort of a relic. When my tech Skully got it, it took him like two months to clean that neck up and make it actually playable.

Generally, I try to find basses that are also playable. That’s the thing: I respect and love the idea that somebody kept them pristine, but on my last tour I took nearly 30 of them out on the road. My collector friends were saying, “You’re crazy! Stick ’em in a vault. Hang ’em on a wall. And I’m like, “Nah, nah, I’m a bass player. I want to play ’em.”

The bass has long been such an unsung instrument. We’ve all heard the stereotypes — the bass player is the dude in the background who’s barely audible and never speaks in interviews. But I feel like you’ve pushed the instrument forward. What drew you to the bass in the first place?

Well, the first thing I played as a young man was a guitar. My next door neighbour had an acoustic guitar that had two palm trees on either side. I don’t even remember what kind it was, but he wanted to sell it and I begged my mother to loan me 20 bucks or whatever it was, and she did and I bought it. I remember sitting in my bedroom trying to figure out songs. The first song I learned was “For Your Love” by the Yardbirds. The second one was “Pretty Woman” by Roy Orbison. Anyway, some of the kids in the neighborhood decided we should be a rock band. We got together in my friend’s bedroom figuring out what songs we would learn. I think we had some old Stones records at the time. But the next day we got a call that the bass player’s mother wouldn’t let him play with us. She thought we were just degenerates. So he was out and they had all talked and decided I was going to be the bass player. I went back to my mom and said, “Look I need a bass because I’m going to be in this band and I’m going to be the bass player.” So I made a deal with her: she would lend me the $35 necessary to buy a Japanese bass. And I would work it off at her discount variety store on Saturdays. And that was it.

Was Alex [Lifeson] in your band at that point?

No. I didn’t know Alex yet.

What compelled you to play the bass the way you do? You obviously weren’t interested in just holding down the the same four notes in the background. You wanted to play leads, like a guitarist.

I was inspired by the bass players I loved in the early days — guys like Jack Cassidy, Jack Bruce, John Entwhistle. These were bass players who had a bold tone and they stood out and did more than just, as you say, hold down the backbeat. I just thought that was cool and so I tried to emulate them. My style is a direct result of the people I was enamoured with as a young musician, which is the case with almost every musician, you know? You’re drawn to certain players and want to be like them, and you hope your influences become so diverse and you have a strong enough personality of your own to contribute that you make your own sound.

What do you think about the state of bass playing today, and the way it’s evolved? Do you like what you hear when you check out new bands?

Well there are more bass players than ever and more bass players that have incredible technique than ever. I mean, there’s sort of been a revolution, especially with women bass players, which I’m really happy to see. It’s great to see so many awesome female and male bass players out there. There seems to be a real trend towards these multi-string basses, which are kind of psychedelic to me. There’s such a production now of five-string and six-string that basses have huge, wide necks. I see it on Instagram all the time; these young bass players, they’re just blowing my mind with their technique. They’re well schooled and they start so young now, so I think it’s going to be really interesting to see what kind of music they make. I’m not sure where it’s all heading but I hope they don’t leave rock behind. A lot of bassists today play a more jazzy style, or rhythm and blues or hip hop style, which is great, but I was always a rock guy. I’d love to hear some guys rocking out.

Any new bass players or bands you like that you can name?

Nah, I can’t really. I listen to more old music these days. [Laughs.] A lot of Bill Evans and jazz guys. It takes me to a new place in my head, so I like that.

Well, after spending all this time studying basses, have you been inspired to pick one up again and start writing new stuff?

Yeah, Im always playing. Like, I went through a period where we were intensely writing the book and I was so busy on a day-to-day basis with revisions and working on the book that I wasn’t playing enough, and I found it really frustrating. So thankfully, you know, when you’re talking about bass you have to also talk about how it sounds, so it forces you to go down there and play it. But yeah, I miss it. I’d like to, once I get past the promoting of this book, I’d like to get back to seeing if I have anything to say musically.

Is there a chance we might ever see some new recordings from Rush?

I don’t think there’s a chance of that, no. But you never know what could happen.

I guess you can’t get everyone on the same page to do it again?

Yeah, we’re all in very different places. You know, Alex and I see each other a lot and we talk about getting together and jamming and stuff like that. It’s just a matter of the right moment. But hang on a second, I have to maintain my dog.

[Dogs heard barking in the background.]

No, no, no, no! You wanna go up here? Sorry, he almost jumped up, which he’s not supposed to do. Sorry about that.

So you were saying, you and Alex are still jamming?

Ah, we haven’t played together since the last tour. But we talk about it. [Laughs.] Talking is good. One day we’ll get around to it.

But it won’t be Rush, it’ll be some of other incarnation?

Yeah, I don’t know. I couldn’t even speculate.

Okay, that’s fair. You know, there are still Rush fans sites being updated daily, to this day. Are you surprised by how obsessed Rush fans continue to be?

Yeah, of course! No one expects that when they join a band. You never know how your music will be appreciated. Certainly, I wouldn’t have thought when I started that this many years later people would still be enthralled with what we did. And it’s very gratifying, especially now to see a whole younger generation getting turned on to our music. All these reissues that come out, that’s really where they’re aimed at — introducing younger people to something that maybe they hadn’t caught onto. And I do see a real need for rock out there. You know, we all need new rock bands. And when there aren’t any they go to the older rock bands.

Yeah, there is certainly a dearth of new rock bands right now. Why do you think that is?

I’m sure they’re out there. If guess they’re having a harder time breaking through. You know, there’s so many different kinds of music and we’ve become a very impatient society due to social media and Instagram and all that stuff. There’s good things that come with social media, but there’s also an attention deficit that’s taking place, so it becomes harder to have the patience to find the new stuff. But I think it’s just a moment, and I think there are so many great young musicians out there. It blows my mind. I mean, I don’t think there’s ever been as many good young musicians out there as there are now. It’s just going to take time for somebody to cut through.

Maybe they just need the right inspiration. Speaking of which, weed is legal in Canada now! Can you tell me about the influence cannabis has had on your bass playing, and Rush’s music?

Marijuana and Rush? Never. Outrageous concept. “A Passage to Bangkok” is just about a train, man! It’s not about anything else. [Laughs.] Yeah listen, I’m really happy that marijuana is being legalized here. It should be legalized everywhere and it’s not going away. It makes people happy, it eases people’s pain, and more importantly, it eases people’s boredom. So more power to it.