During the first week of pandemic-induced lockdowns last March, I bought a sewing machine. I had plans to construct pants and bags, and so I was sure that I’d learn how to use it and have something to show off to my friends when I emerged back into the world. I wasn’t alone. It seemed like everyone on the Internet was speculating about what might be created with all this newfound free time. As our respective sewing machines collected dust, it became clear that, for most of us, forced isolation was the ultimate killer of creativity — but not so for Toronto-born, New York-based painter Keiran Brennan Hinton.

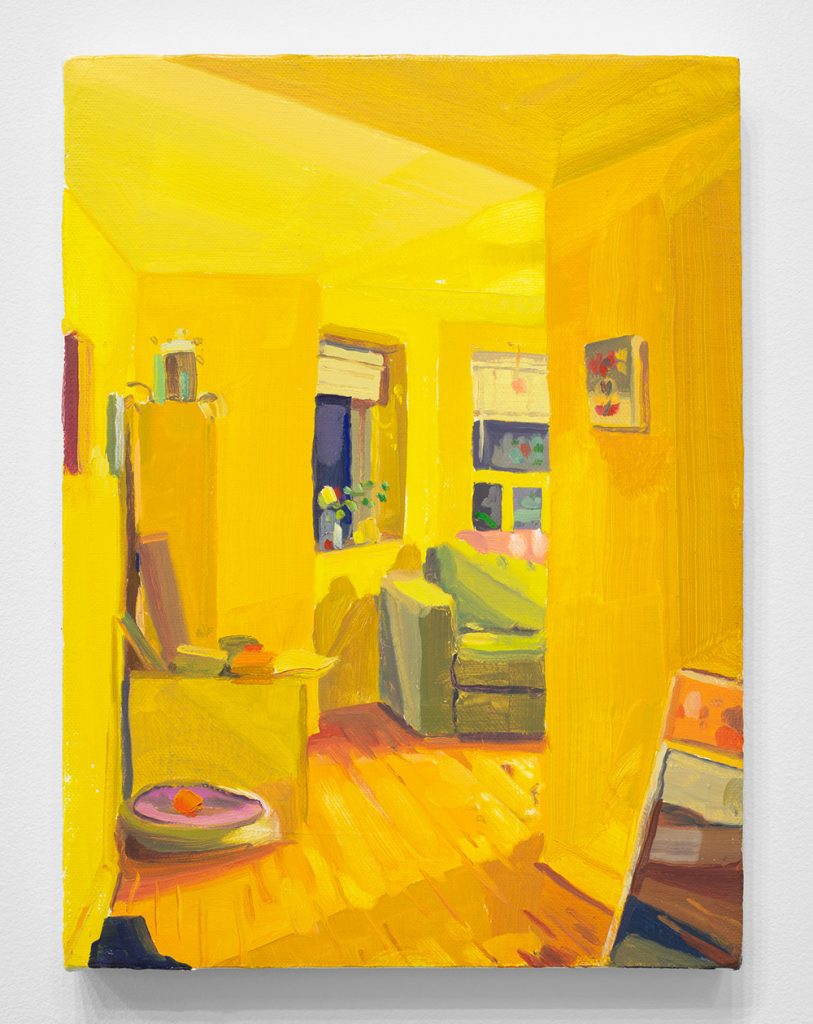

Just before the arrival of lockdowns last year, Brennan Hinton and his newly retired mother bought an 103-year-old Ontario schoolhouse. Its edges were rough. The water wasn’t drinkable. Floor joists were rotting. A washroom didn’t even exist. While the pair spent the pandemic’s early days fixing up the property, Brennan Hinton was also busy painting, setting his easel up in and outside of the schoolhouse, observing daily life in isolation and documenting the schoolhouse’s slow transition into a home.

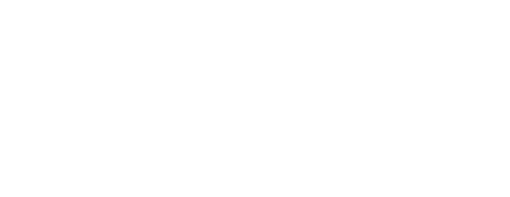

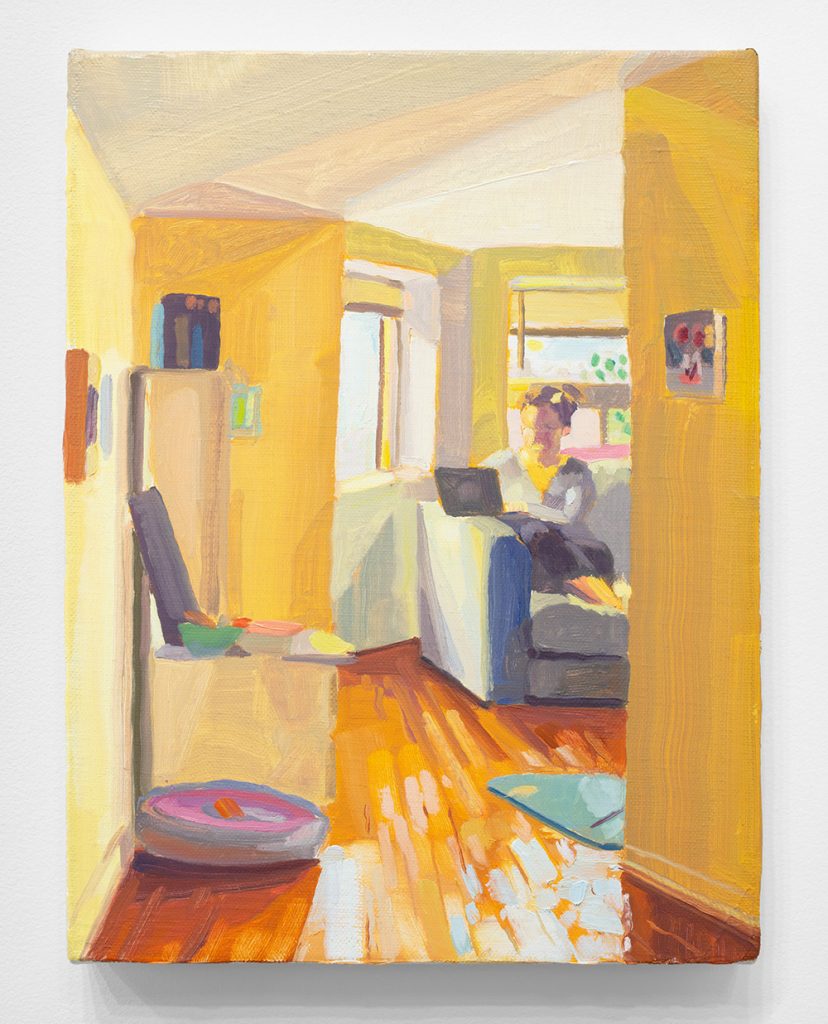

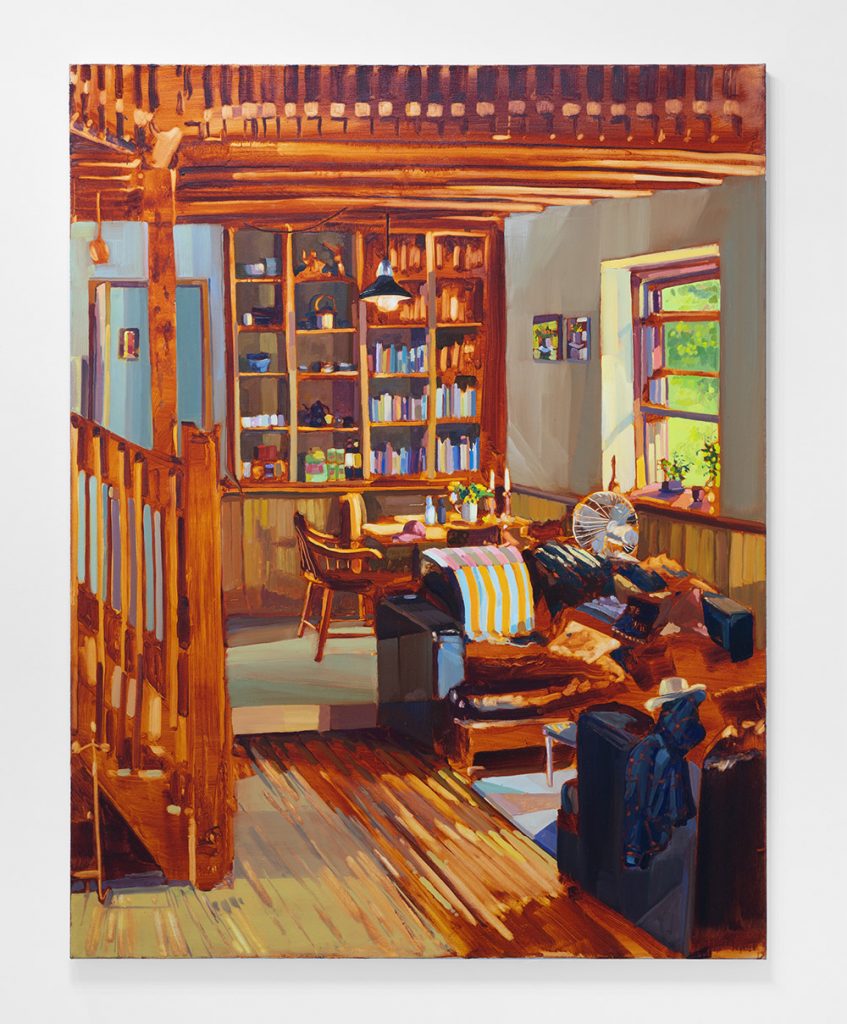

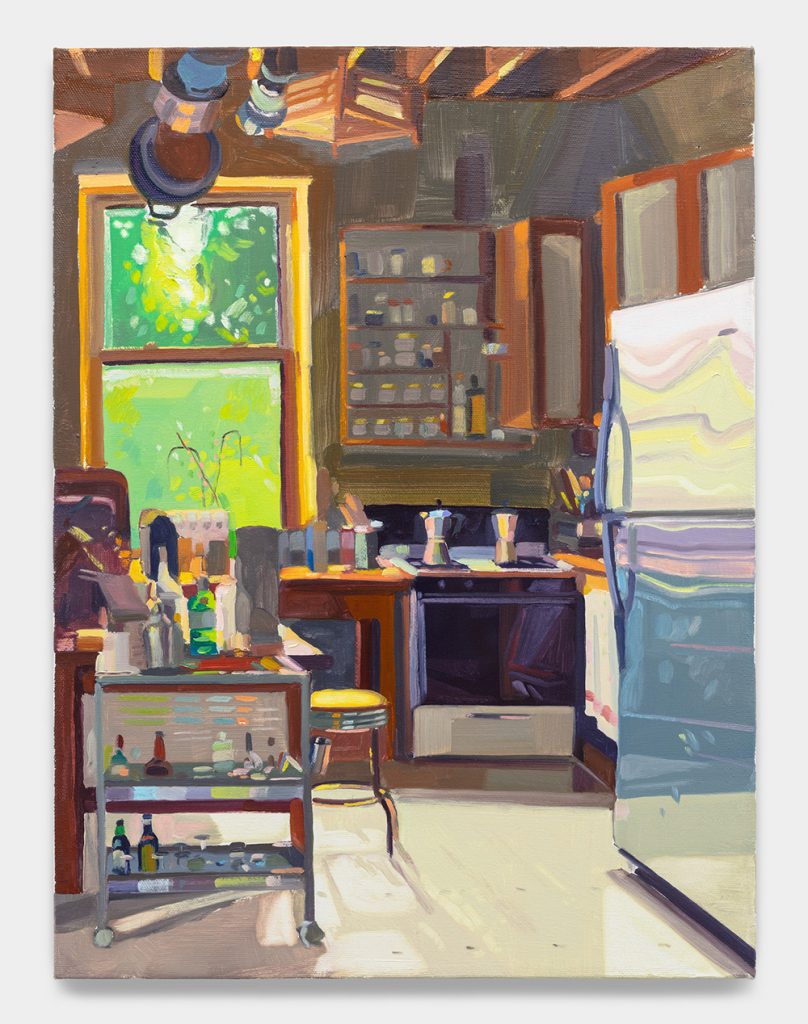

The resulting paintings are part of Towards Sentimentality, a new solo exhibition currently hanging at the Charles Moffett Gallery in New York City. While 11 of the show’s 18 paintings capture life at the schoolhouse, the remaining 7 were made following initial lockdowns, when Brennan Hinton would stay at his new partner’s apartment in Toronto. While nearly all Brennan Hinton’s paintings are of interior spaces — and he certainly has an eye for architectural detail — they are anything but steely. Instead, they investigate the concept of home as a container for human connection and as a site for relationships. At every turn, they capture the trace evidence of humans, even if people are rarely seen on canvas.

From New York, Brennan Hinton spoke with Sharp about interiors, observing the everyday, and the role of sentimentality in art.

First off, what’s the story behind this new series of paintings?

So basically all these paintings started when I came back to Canada last year. My mom and I had been looking at the possibility of getting a house together. She was retiring [after being] an elementary school teacher her whole life and I kind of wanted a studio in Canada. We found this one-room schoolhouse north of Kingston and I came back last March just to see it and then everything shut down. We got the place. I ended up staying and that led to this whole series of paintings. So these have been made over the past year, primarily at the schoolhouse. I was also making little paintings when I’d go into Toronto to see [the person I had started] dating at the beginning of the pandemic, so I’d bring these small canvases and make paintings at her place. Obviously, we were spending so much time indoors — everyone was — that it was kind of about using these paintings as a way of developing a relationship and containing intimacy. I was just really thinking about the interiors that we’re living in and spending time in, as both a reflection of our behaviours and mental states, but also the ways that relationships and personalities kind of get imbedded in the spaces that you live in.

Obviously, our notions of home have shifted considerably over the past year, but your interest in interior spaces pre-dates the pandemic, right?

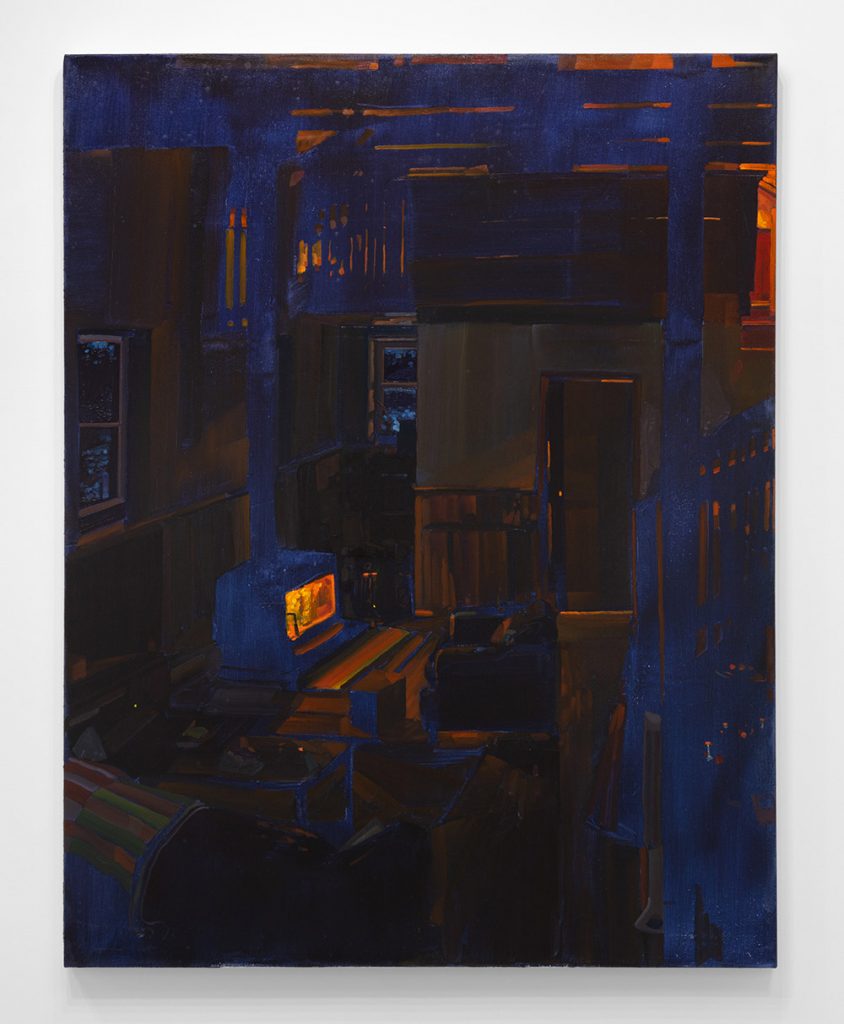

Totally! I don’t want these to feel too weighted in the direction of being just from the pandemic. I have been painting interiors for a long time. [I’m interested] in the traces that you leave behind in a space and using painting as a way of recording that. They’re paintings about people in many ways, even if they often don’t include anybody. It’s more trying to intuit what it feels like to be in a place as opposed to articulating every detail of it. So [for example], up at the schoolhouse, the only heat source is our wood stove — and December in rural Ontario is really cold — so I liked the idea of setting up an easel and making a painting of this thing that you feel super connected to.

But one thing that did change for this body of work was I made them all from life. In the past, I had never really been able to make large paintings from observation; they were from photographs or composite images and memory. I was making them in my studio in New York, as opposed to the small ones which were always made from life. For the small ones, I’ll set up an easel and make the painting in one sitting over maybe 3 or 4 hours. You have to paint everything as it’s changing inside of that time — so a light goes off, or the sun or the shadows move. It’s this practice of being super attentive to all those things. But then what happened with the schoolhouse is that I could make the large paintings from life as well. And that really shifted things. I could focus on finding moments of intimacy within a larger space.

How do you identify a moment that you want to capture, or is totally instinctual?

There’s a couple different answers. I went to this residency a couple years ago in Idaho that was called the James Castle House residency. He was an artist who lived in a small shed and drew his surroundings for his whole life. He was deaf and he never learned to speak, but he has this whole record of drawings that became his body of work that documents basically his whole relationship of communicating with the world. He drew his same 100 square foot shed over and over and over again. But through the repetition, they became incredibly detailed and intimate, and they become factual in a way. They feel true.

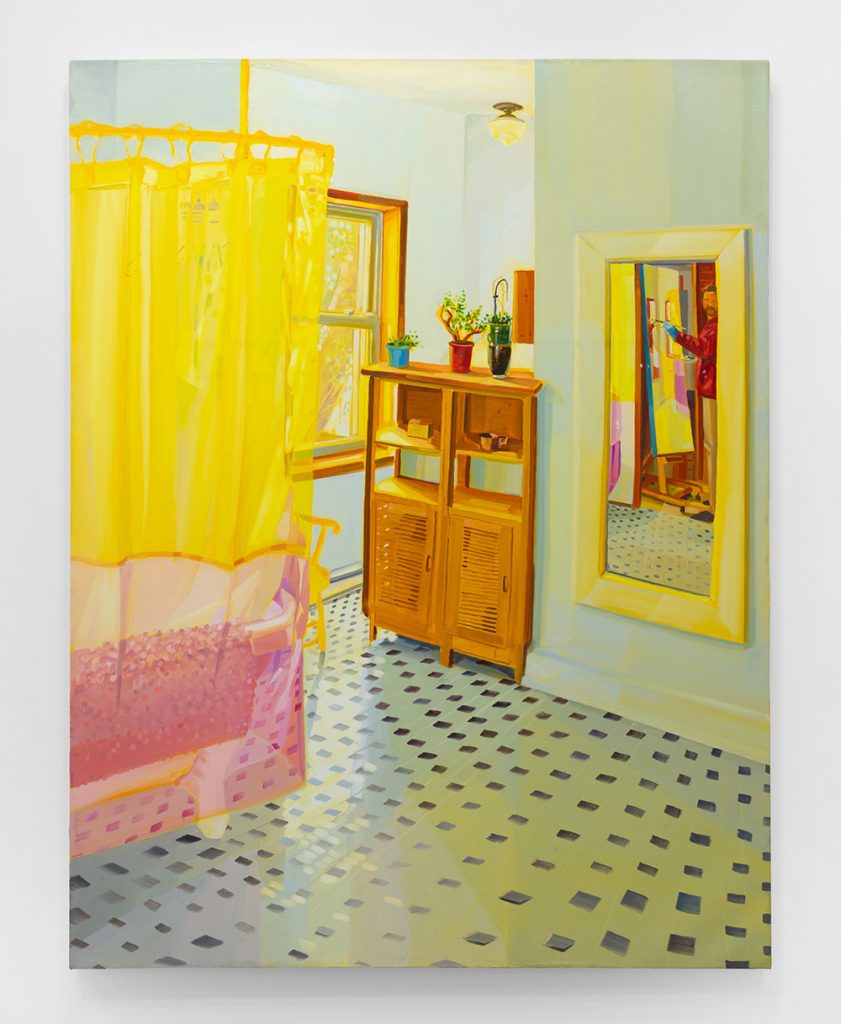

Other times, it’s just moments that happen; things that you’d dismiss [or] are unremarkable. So, [for example] my girlfriend’s place has this red shower curtain and when you get the light through the window, you get this wash of red. It becomes super beautiful. And I thought that would be a cool idea for a painting. I often try to find moments that feel really worth looking at.

I remember reading something by the photographer Alex Webb – I think it was Webb – about how difficult it is for him to photograph at home because everything kind of gets blurred by familiarity. It’s really hard to see what’s unique or interesting about a place that you know deeply. But with this series, you flip that on its head and really investigate these spaces that you’re spending so much time in.

Yeah, that’s a super interesting way to think about it. For me, both of these spaces — whether it was the schoolhouse or my girlfriend’s place — were unfamiliar enough that I would discover new things while painting. There’s a term — I think it’s Swedish — like home-blindness, and it’s that you leave things in place and you just forget that they’re there. So painting is almost a way of reminding or at least staying in touch and being attentive to those things. So I kind of like that idea of, yeah, turning it on its head and focusing on the space that you’re surrounded in every day as a way of feeling grounded and like a part of that space. When my mom and I moved into the schoolhouse, there was no bathroom so we had to build a bathroom together. So [there’s one] painting kind of become a dedication to that experience of laying tiles, building the frame, doing all that stuff.

The light is incredible.

That’s part of making them fairly quickly. I want them to feel very much alive, like you just opened a door and walked into this place.

They do feel alive. To me, even if people aren’t typically present, there’s still a very strong sense of narrative due to the items involved and the organization and the general feeling of the space.

And I think that narrative is up for the viewer to decide. I can come up with my own meaning for the paintings, but I don’t really want to proscribe that onto someone who’s looking at them. I also want them to feel like they’re first-person. So, the person who is looking at the painting is standing in the same place that I was making the painting. And I think there’s something neat that happens in that transferring of place, where you — the viewer — develop your own relationship or narrative of what’s going on. How do you make somebody feel involved in the thing that you’re looking at? As opposed to being apart from it. I feel like that’s sometimes such a barrier at museums or when viewing art in general, feeling distance from it or feeling a sense of intimidation. For me, it’s really important to have the paintings become accessible and approachable, and how to let somebody in on this little world that you’ve lived through.

That ties into something you said previously: that this show is expressing a level of vulnerability that you haven’t shown before. Why does this series feel more vulnerable than your past work?

For me, this whole series was about reconnecting with my mother and building a new relationship and using the interiors of the houses to facilitate those relationships. These paintings are a document of that time. There’s a vulnerability in that. The title of the show is Towards Sentimentality and sentimentality is such a tricky word in art because it’s incredibly taboo; it’s almost a pejorative in art school to be sentimental. But I have kind of just accepted that these are sentimental paintings. I’m okay with that. [In one], there’s this apron that I got my mom for mother’s day or there’s a blanket on the back of the couch. Those are sentimental things and I think painting has a way of speaking to sentimentality — and not in a cliched way, but more in a sincere and honest reflection of the things that we do for the people that we’re around. It’s about sharing intimacy, sharing a daily life and being pretty straight forward about depicting things just as they are.

At the start of the pandemic, so many people had plans and ambitions for what they’d achieve with a ton of free time. But I think for most of us, that motivation took a nose-dive when we realized how much social connections and just being out and about in the world sustains us. But for you, coming from both New York and Toronto, was that forced isolation a naturally productive time?

It was pretty motivating. I definitely picked up those hobbies at the beginning, like doing puzzles every day or whatever it was. But I found the lack of distractions, whether in rural Ontario or at my girlfriend’s place, super helpful to just be able to slow down and not really be around anything else. And I’m finding being back in New York right now that it’s very hard to stay focused and on practice when there is so much to do and so much to see. I think I’ll be mainly in Canada moving forward pretty much for that reason. [At the schoolhouse,] things just started to feel fresher, and they could take longer. These paintings didn’t need to be seen or shown. There was no pressure on them, basically. Because the paintings are of everyday things, they have to feel loose or casual for them to actually work. I think if they’re overthought, they start to feel too tight.

The show opened during the first half of June. What’s the reception been like so far? And what’s it like to be showing in a physical space again?

It’s felt great. We all transitioned to a lot of online viewing rooms over the past year, but after a year of that, it’s been great to be in a space and see how people interact with [the paintings] in a way that is completely different than if you’re just viewing things on Instagram or a website. So yeah, the reception has been really, really good. It felt funny and really personal too because I made these paintings in such a different scenario than New York but now they exist in the city all together as one. And when the show ends, they go to all these different pieces. So it’s kind of this funny thing: paintings get made in isolation, they become public, and then they go back into isolation when they go into somebody else’s home. But I like that journey that they go on.

Lead image: Elizabeth Brooks