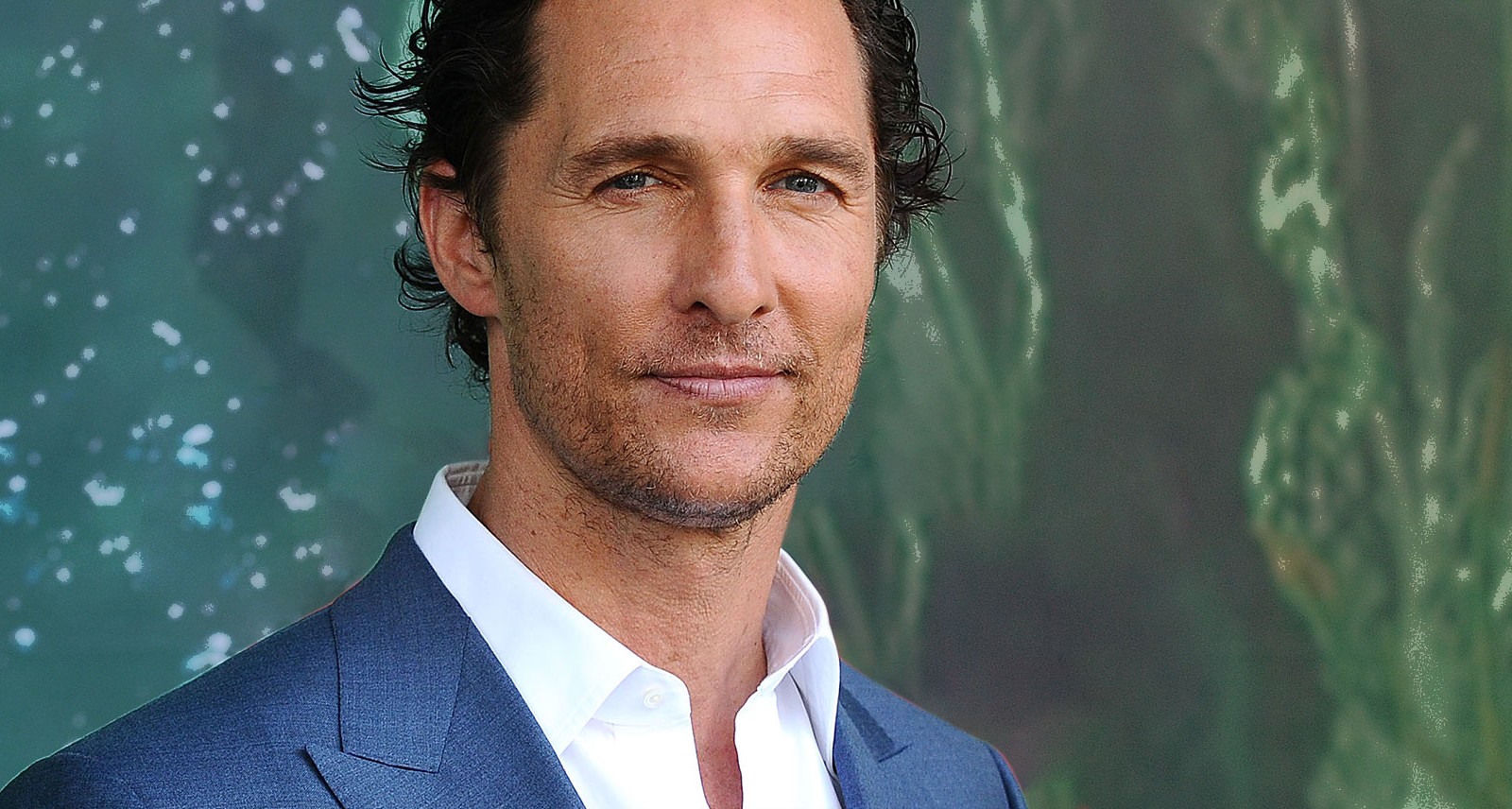

Matthew McConaughey is driving. He’s cruising down the freeway, has been for hours, deep in the heart of Texas. He’s talking as he goes. Philosophizing. About life, about fatherhood, about the meaning of success.

“I’ve learned some things worth sharing,” he intones in that smooth, disarming drawl.

At this point, you’re probably picturing that Lincoln ad you’ve seen 12 times too many. I certainly am, even though I know that this is something else entirely. You see, McConaughey isn’t wearing that familiar dark suit. Instead, he’s in a black trucker hat and a faded orange tee bearing the words “just keep livin” — lack of capitalization and Gs intended — which is both his personal mantra and the name of his foundation. He isn’t speaking to a camera; he’s speaking to me, over slightly fuzzy Bluetooth. And his streams of consciousness aren’t going uninterrupted. Every now and then he pauses to say something to his 8-year-old son Levi, who’s riding shotgun.

The McConaugheys are on their way from Austin, where they live, to Arlington, to watch the Texas Rangers take on the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. It’s that most simple and sacred of summertime traditions — a father and son taking in a ballgame — but it’s also more than that, because this is Matthew McConaughey we’re talking about. The Rangers are hosting an event in support of the just keep livin Foundation, and McConaughey is scheduled to have a photo op with donors and speak to a group of local students prior to the game. And before that, of course, he’s in the car, doing an interview for the cover of this very magazine.

Nothing, not even a father-son ballgame, is simple with McConaughey. He is, with all due respect to the ever-industrious James Franco, perhaps our most malleable and wide-ranging star, countless things to countless people at all times, a human homonym, impossible to define.

Over the past couple of years, especially, McConaughey has developed a penchant for simply popping up in delightful and unexpected ways. He’s taught classes at the University of Texas at Austin, his alma mater, and given rousing pep talks to the school’s football team before big games. He was a dedicated Team USA superfan at the Rio Olympics, in the stands and on his feet for everything from swimming to women’s rugby. And, of course, there were those Lincoln commercials, earnest and thought provoking and perfect spoof material for all the late-night talk shows. At this point, with the exception of late-career Bill Murray, there’s perhaps no living actor more widely beloved for his distilled himself-ness, as random as it may be.

Which is fine, except that Bill Murray is 68 years old, and McConaughey is 46, two years removed from winning an Academy Award for his powerful performance in Dallas Buyers Club. This should be the prime of his career. But ever since the McConaissance — more on that later — he’s been faced with an interesting question: how do you follow up a rocket-powered ride back to the top of Hollywood? Where do you go once you’ve scaled the mountain and planted your flag?

So far, McConaughey’s answer has been imperfect, at best. The two live-action films he’s released since 2014’s Interstellar — the unofficial coda to the McConaissance era — have been, to be charitable, well-intentioned missteps. There was last year’s mawkish tone exercise The Sea of Trees, which was alternately booed and laughed at by critics at Cannes; and this past summer’s Free State of Jones, a Civil War epic that was far more civil than epic. It began to seem possible that McConaughey was destined for a slow fade into the background, a feel-good story we’d recall fondly from time to time, like Captain Sully or Bernie Sanders.

But a real response seems to finally have arrived in the form of this month’s Gold. It’s a Harvey Weinstein-backed, based-on-a-true-story prestige film that’s garnered Oscar buzz virtually from its inception. And it looks set to snap the next phase of McConaughey’s career sharply into focus.

It’s kind of incredible to consider how much of Matthew McConaughey’s enduring public persona was determined in his very first film appearance. In 1993, Dazed and Confused delivered McConaughey to us fully formed, in that charming, cerebral troublemaker mode, complete with “Alright, alright, alright,” and “Just keep livin’, L-I-V-I-N,” cued up and ready to become lifelong catchphrases.

That period had unforeseen lasting effects on McConaughey, too. He lost his father, Jim, at 22, just days into filming. The elder McConaughey famously died while making love to his wife, whom he’d divorced twice and married thrice over the course of his life. Drafted by the Green Bay Packers in 1953 but released before ever playing a game, Jim ran an oil pipe supply business. But to hear his youngest son tell it, he’d held dreams of striking it rich through somewhat less conventional means.

“My dad almost wanted to be a mafia guy, but he wasn’t. You know what I mean?” McConaughey says. “He once bought a watch from a guy in a white van who was pawning off microwaves, hair dryers and washing machines. It was supposedly a $22,000 watch, and Pop got so much excitement out of that — getting what he thought was a good deal in a somewhat shady way.

“It’s the same reason he once invested in a diamond mine in Ecuador. There were no diamonds in Ecuador! But for my dad, it was about the adventure of it all. That was the fun of it. He would rather do a bad deal and lose money than do a good deal with boring credentials.”

His father’s audacious spirit, McConaughey admits, has been present in nearly all of his most memorable roles: True Detective’s Rust Cohle, Dallas in Magic Mike, Dallas Buyers Club’s Ron Woodroof, even his brief, chest-beating cameo as Mark in The Wolf of Wall Street — grifters, dreamers, soothsayers all.

“I love that kind of obstacle, man, something to overcome,” McConaughey says. “A lot of my characters, it’s unclear if they’ll survive. They have to fight to stay alive. I like the outcasts that don’t live by the social norms or accepted graces. They live on the outskirts, man. They have their own rulebook for how they choose to play the game.”

In that sense, it’s easy to see what drew him to Gold, a Scorsese-esque rags-to-riches-to-dire-complications whirlwind that follows McConaughey — with grossly thinning hair up top and an extra 50 pounds in his paunch — as Kenny Wells, an unlucky hustler who uncovers the titular substance deep in the jungles of Indonesia. “Very few times that I’ve read a script once and just immediately saw it for me. But this guy Kenny Wells, I fell in love with his heart. He’s a real dreamer, a real salesman. He’s got a great line: ‘A bird with no feet sleeps on the wind, and if he ever lands, he’ll die.’

“You just got to keep it going,” he continues. “You keep throwing the ball up there, even when you’re on fourth and 16. And Kenny Wells, he keeps throwing it up to himself and catching it.”

It sounds a little like the position McConaughey found himself in at the turn of the decade. After spending the ’90s as the most promising young actor of his generation — sought out for juicy roles by the likes of Steven Spielberg, Ron Howard, and Robert Zemeckis — he settled into a postmillennial malaise, pigeonholed as shirtless flotsam in a string of increasingly cringe-inducing rom-coms: The Wedding Planner, Failure to Launch, Ghost of Girlfriends Past, to name but a few. By 2010, just about everybody had written McConaughey off as a cautionary tale, a great talent gone to waste. Everybody but the man himself, of course.

And thus began the McConaissance. In 2016, it’s the stuff of American folklore, an origin story as familiar as Bruce Wayne’s or Peter Parker’s: McConaughey, condemned to the outskirts of Hollywood, began a slow and steady march back to its centre. He kept throwing the ball up there and catching it, one critically acclaimed performance at a time, all the way to a golden statuette.

He claims, now, that there was never any grand scheme, that he had “no expectations or plan,” that he was simply ready for something different and started taking jobs that turned him on. But make no mistake: that was the confident charge of a man with something to prove.

And now it’s led him here, to Gold. You could be cynical about this movie, see the weight gain and the bald cap and the exotic locale as nothing but mere Oscar bait, another dramatic body transformation because Dallas Buyers Club worked the first time. But you’d be wrong.

For one thing, this was a hell of a lot easier than the weight loss he endured for Dallas. “Burgers and beer,” McConaughey says of his diet plan for Gold. He got up to what he calls a “soft 217” by “just saying ‘yes’ to everything for five months.” (At this point, Levi chimes in from the passenger seat: “I want you to play another character like Kenny Wells, dad. You were so fun.”)

But more importantly, when you see the commitment McConaughey displays in this movie, the sheer breadth of the performance he turns in, you’ll realize there’s nothing the least bit stunt-like about it. Instead, it marks the beginning of Matthew McConaughey’s third act, in which he leaves behind permanently the notion that he’s just a pretty face, moves past being simply a damn fine actor, and embraces his inner weirdo. If Gold is any indication, the next decade could very well be the most fruitful and eccentric of McConaughey’s career.

Though, as is always the case with McConaughey, it hardly tells the whole story. That would be too simple.

…

Gold might be the most buzzed about of McConaughey’s current projects, but it’s not his most personal.

You could make a passable case for Sing, in which he voices an optimistic koala attempting to save his family’s theatre. It’s just the second animated movie of McConaughey’s career — the first was August’s Kubo and the Two Strings — and he’s proud to have finally made movies that he can watch with his three children, and that are relevant to their lives.

But strangely enough, the most near-and-dear thing McConaughey has worked on of late might actually be an ad campaign. Earlier this year, it was announced McConaughey would become the creative director for Wild Turkey bourbon. Campari, Wild Turkey’s parent company, had approached him originally to simply appear in some commercials, but McConaughey had greater designs.

“I didn’t just want to be the face of the brand,” he says, his voice rising with noticeable gusto. “In 30 seconds, nobody wants to just be told what to drink by some actor. There’s nothing artistic about that. I had ideas, man. I was really interested in creating a mood, a vibe, an adventure.”

McConaughey’s thrown himself completely into the job — he directed a short documentary at Wild Turkey’s Kentucky distillery, and says he has ideas for the branding and presentation of bottles. “I did get more than I bargained for, but in a great way,” Melanie Batchelor, Campari’s vice president for global spirits, told The New York Times about the collaboration in August. “Personally, I have been completely overwhelmed with his level of commitment.”

“What other subject would it be best to know something — to know a lot about — more than ourselves?”

The highlight is a 30-second spot, conceived, written, and directed by, not to mention starring, McConaughey. In it, a lady swirls through a rambunctious juke joint party, glass of Wild Turkey in hand, before winding up outside at a campfire. She delivers the drink to McConaughey, who’s playing a baby grand piano beneath a tree. “It’ll Find You,” the tagline reads.

“It’s the idea that if you’re being authentic — not trying to be somebody else, doing your thing, having a good time — there’s a really hot lady in a black skirt who might bring you a Wild Turkey. It’ll find you.”

That idea of authenticity, I posit, seems to inform everything McConaughey does.

“I try to know myself as well as possible,” he says. “That’s what Malcolm X says, you know? Know thyself, man. It’s a constant challenge, because life changes. You fail. You screw up. I try things that don’t work. There are areas where I get complacent and lazy. I definitely don’t have it figured out. But it’s an inch-by-inch process. You have to stay doing the work. Because what other subject would it be best to know something — to know a lot about — more than ourselves?”

I ask what he knows about himself, definitively, at this point in his life.

“I know where I stand,” he says. “I know I have plenty more to accomplish before I’m through. I know I’m lucky to have a wife who doesn’t want to change me. I know there are people in my life who I — uh, hang on a second.”

He drops the phone away from his face. By now, the McConaugheys have arrived at Globe Life Park, the Rangers’ stadium, and I can vaguely make out the familiar, harried sounds of a pregame ballpark: people rushing to their seats, to the bathroom; announcements booming over the intercom; a program vendor making his sales pitch.

“You want anything to drink, or just the chicken fingers?” I hear McConaughey ask his son.

He comes back to the phone eventually, of course, to finish the interview. But it seems like he’s already given me as good an answer as any.