Harnarayan Singh is probably the most famous fellow from Brooks, Alberta, a rural town of 14,500 about two hours southeast of Calgary. Though it’s known as the City of 100 Hellos, Singh, a child of Indian immigrants – his dad has a PhD in math and seven (yes, seven) postsecondary degrees, and his mom is a former principal and social studies teacher – could count the number of kids from visible minorities on one hand. Still, he found common ground with his peers the way so many Canadian kids do: through hockey. But when his parents bought him a microphone to mock-announce Oilers games, they unknowingly nurtured their son’s obsession with becoming a sports broadcaster – a field largely dominated by white guys.

In 2008, Singh was working for CBC Calgary when he caught the eye of former goalie and announcer Kelly Hrudey, who put him on the network’s radar as a potential new voice. He was eventually anointed Punjabi-language host of Hockey Night in Canada, a historic move that would see Singh as the first to announce an NHL game in Punjabi for TV and the first Sikh Canadian to broadcast a game in English. But Singh’s story isn’t just one of persistence and passion: It’s a distinctly Canadian narrative about an immigrant kid’s mission to broaden the boundaries of a national sport to include those who never saw a place for themselves within it.

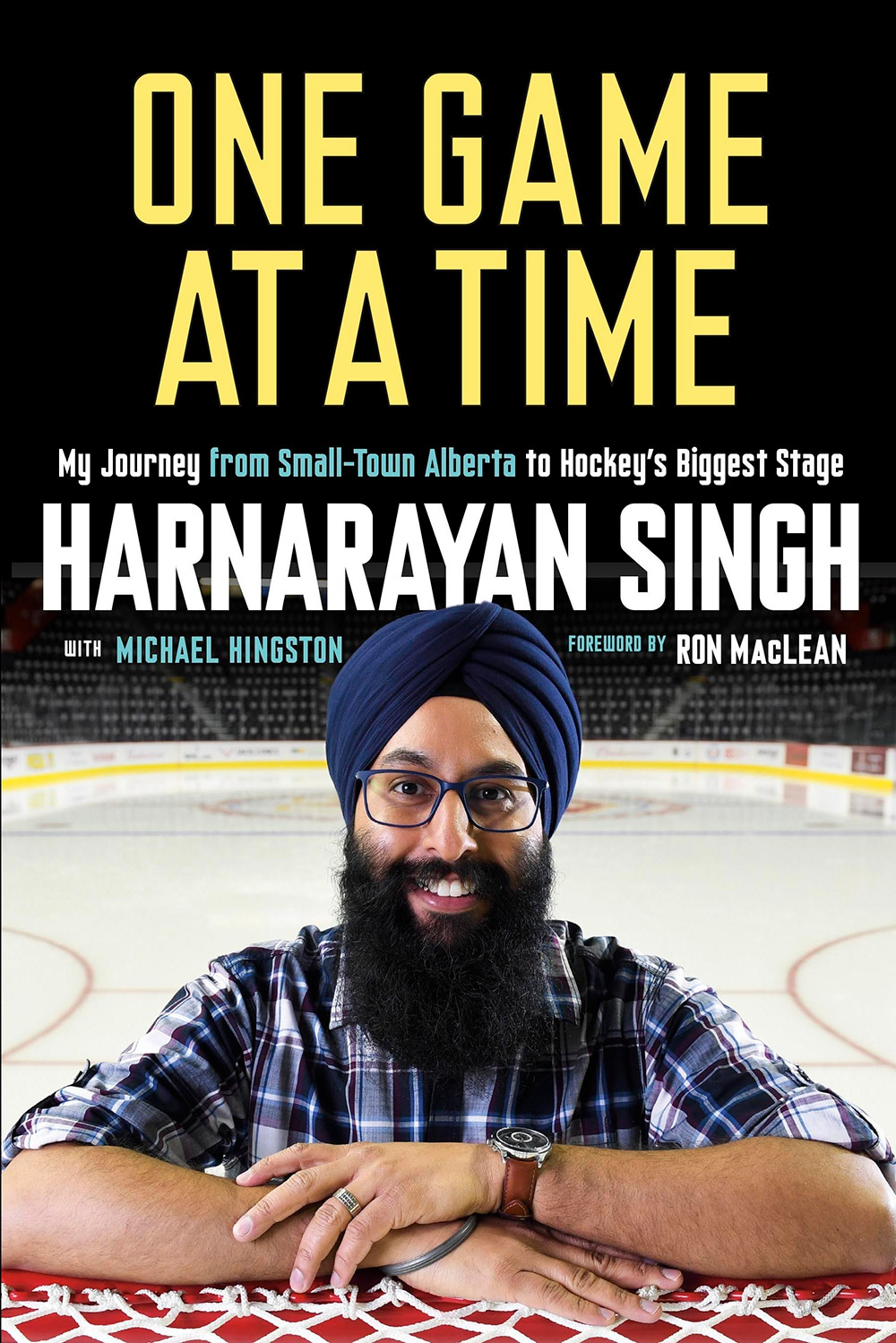

In his new book, One Game at A Time, Singh reflects on his illustrious career, charting his journey from a Gretzky-obsessed kid to beloved hockey commentator. Here, he tells us about the importance of representation in sports and media, career highlights and hockey’s ability to bring Canadians together.

Why a memoir? Why now?

To be honest with you, I was actually quite amazed when McClelland & Stewart and their team approached me to write this book. But as we progressed in our discussions, I realized just politically, too, the climate, [I wanted] to show that there is a story of diversity that can prove that it works. We can we can live together harmoniously in one nation and be different, but still have everything work real well together. I’ve also realized that having students come up after I speak [at their schools] and say that they never had imagined there would be a place for them in mainstream media or in sports. After seeing me there, it gave them hope or it made them realize that they would have a shot at it too. That in itself makes all of this worthwhile.

What was it like growing up being a Sikh kid playing hockey in rural Alberta?

For me, in Brooks, I can tell you that there weren’t very many kids like me at all. Especially with my situation, where you wear it on your sleeve and you have the turban, [and you’re] quite different from everybody else in terms of the music I listen to [and] the language we spoke at home, the food we ate… It wasn’t very diverse, and I did stick out. But I can tell you after reflecting back on the journey, my experience growing up in Brooks would have been drastically different had it not been for hockey. I think really early on, my obsession with Wayne Gretzky, my obsession for the sport, it really helped me break the ice with classmates and teachers. When you find common ground with someone who’s different from you got that forgets about all those differences.

Besides the Bonino call, what’s your most memorable career highlight?

I think, even as a broadcaster, no matter who you are, what your background is or how you look, to be able to be invited by the Stanley Cup winning team to participate in their Stanley Cup parade in front of 400,000 people. We had signs that said We Love Hockey in Punjabi and Bonino calls everywhere.

Personally, I would say [another] moment that really sticks out is the 2016 World Cup of Hockey in Toronto. I was asked to speak at the Hockey Hall of Fame as a keynote speaker for one of the first one of the sessions they were having there, like a symposium about the state of hockey on different topics. And I was asked to speak about diversity and inclusion in front of such a distinguished audience where the commissioner was there and a lot of the executive producers, managers, presidents of Sports Net, and so many different Hall of Famers, and just everybody a lot of different amazing people in the hockey world.

On my first ever trip to Toronto when I was nine years old, my mom made sure to take me to the Hockey Hall of Fame because she knew how excited I was to see it. And however many years later to be asked to speak there with all those plaques in the background, that moment probably sticks out as well.

Will you be doing this forever?

Yeah! I’ve been within the Hockey Night family, this is my 13th season. [I] want to make this forever, and I’m very thankful that I’m progressing towards that. I’m so passionate about what the show brings to the community, [about] what it means. It goes much deeper than just the actual game in terms of bringing families together, having diverse families participate in something so Canadian. I think it’s nation-building because we are people from so many different backgrounds coming together to support the same goal, the same cause, the same passion.

But I also feel that in the day and age we are in, it also has such a big impact to have representation on the mainstream side, too, so that we can change the narrative of some of the ignorant people out there who say “go back to where you came from”. This is just as much my country, if not even more, than it is to the person saying that. They don’t know my family’s history here, how patriotic I am about Canada. I guess more recently I’ve realized how much more important this is. And you know, it’s not just a passion project anymore – there’s a lot more meaning to it.